Deaccessioning as an essential part of museum practice

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Martina Caruso, Director of Collections and Rob Wilson, Art Director and Operations Manager, Bowne & Co.

June 10, 2021

The story we’re about to tell you came out of the process of inventory, research, and investigation of the history of collecting items related to printing history, often displayed, interpreted and used at Bowne & Co. It follows the life of one printing press and its connection to three different museums on two coasts. When we thought of telling a larger audience about this adventure we had a few points that we wanted to highlight: first, how impactful long-term loans can be; second, how important and healthy it is to refine a collection; and third, how critical it is to build a network of peers and professionals in our field(s).

The South Street Seaport Museum as a whole celebrates the community and economy that grew up around the port of New York. Throughout the 19th century, every business and transaction needed receipts, bills, advertisements, and certificates; printing offices like the historic Bowne & Co. filled that need. The Seaport Museum holds over 28,000 artifacts composed of a wide variety of mediums and topics, including a printing history collection built around a working variety of printing presses, as well as a vast holding of printing equipment, printing types, photo-engravings, and hand-cut wood blocks. This collection preserves the tradition of small-batch job printing in the 19th century, while keeping an open and active dialogue with contemporary practices of printmaking and graphic design communities.

Since 1975, Bowne & Co. have taken responsibility for holding artifacts and equipment in the public trust on behalf of the Seaport Museum. The nature of most items in this collection, particularly the printing presses, requires that they be operated by trained staff in order to better preserve them, and the staff at Bowne & Co. care for the working printing equipment in collaboration with the Museum’s Collections Department. These objects are considered part of the “Working Collections” of the Museum, used and put in action on a daily basis by trained staff members for the artifacts’ own preservation, and the preservation of the related traditional skills.

As part of the first wall-to-wall inventory of the Museum’s collections in over two decades, a full catalog of accessioned printing presses and printing equipment has been ongoing since the fall of 2015. The process includes looking at the equipment in the print shops, photographing them and assessing their condition, as well matching objects with their acquisition documentation, provenance, exhibition, publication, and loan history. Through this process we uncovered many old incoming and outgoing loans that provided us with a full picture of the curatorial scope of our entire collection.

Objects come into a museum’s collections because they are determined to have value—cultural value, artistic value, or educational value that gives us special understanding of the past. For the Seaport Museum, the origins and growth of New York City as a world port is integral to our mission. However, sometimes objects that were added to the collection are found to fall outside of our mission and have little New York City significance or storytelling value. The process of reviewing and removing items from a museum’s collection is known as deaccessioning. A healthy and necessary practice, deaccessioning allows museums to better care for the collections that best reflect their mission, to reduce duplicate items, and to better maintain safe environments for the collections that remain.

Bronstrup Philadelphia Iron Hand Press

The star of this deaccession adventure is a Bronstrup Philadelphia handpress, which represents a great technological shift in printing technology, moving away from presses made from wood, to presses made from iron. While iron presses were vastly heavier than their wooden counterparts, they were also much stronger, and allowed for bigger printable areas, and faster operation. The 1820s saw many competing patents for presses that sought to find balance between strength, simplicity, and ease of use. In the United States, the most popular style of iron hand press was the Washington, invented by Samuel Rust in 1821. The Washington Press became the favorite of many printers of the time due to the strength of the toggle mechanism, which produced a large mechanical advantage in a relatively simple and compact package.

The Bronstrup Philadelphia Press is a press with two names. Initially designed by Adam Ramage as the Philadelphia Press in 1833 or 1834, the press was designed as a wrought iron construction, rather than the popular cast iron as seen in the Washington. This allowed the press to retain its strength, while drastically reducing weight. This weight reduction saw the Philadelphia press rise in popularity with printing outfits setting up in western states.

Adam Ramage was succeeded by Frederick Bronstrup upon his death in 1850. Bronstrup made small changes to the Philadelphia press, mainly in modifying the toggle mechanism to more closely resemble that of the Washington Presses. This new press was sold as the Bronstrup Press until 1875.

Bronstrup Philadelphia Hand Press engraving by Jon DePol (1913-2004), published in “American Iron Handpresses” by Stephen O. Saxe, Oak Knoll Books, 1992.

This press was on view at Bowne & Co. between 1975 and 1982, and after only 7 years on-site it started its “career” as a representative of the Museum in two other cultural institutions.

Outgoing Loan History

The Bronstrup was on loan to the Fairleigh-Dickinson University, in Teaneck, New Jersey, from 1982-1999, and since 1999 it has been on loan to the Gomez Mill House, in Marlboro, New York.

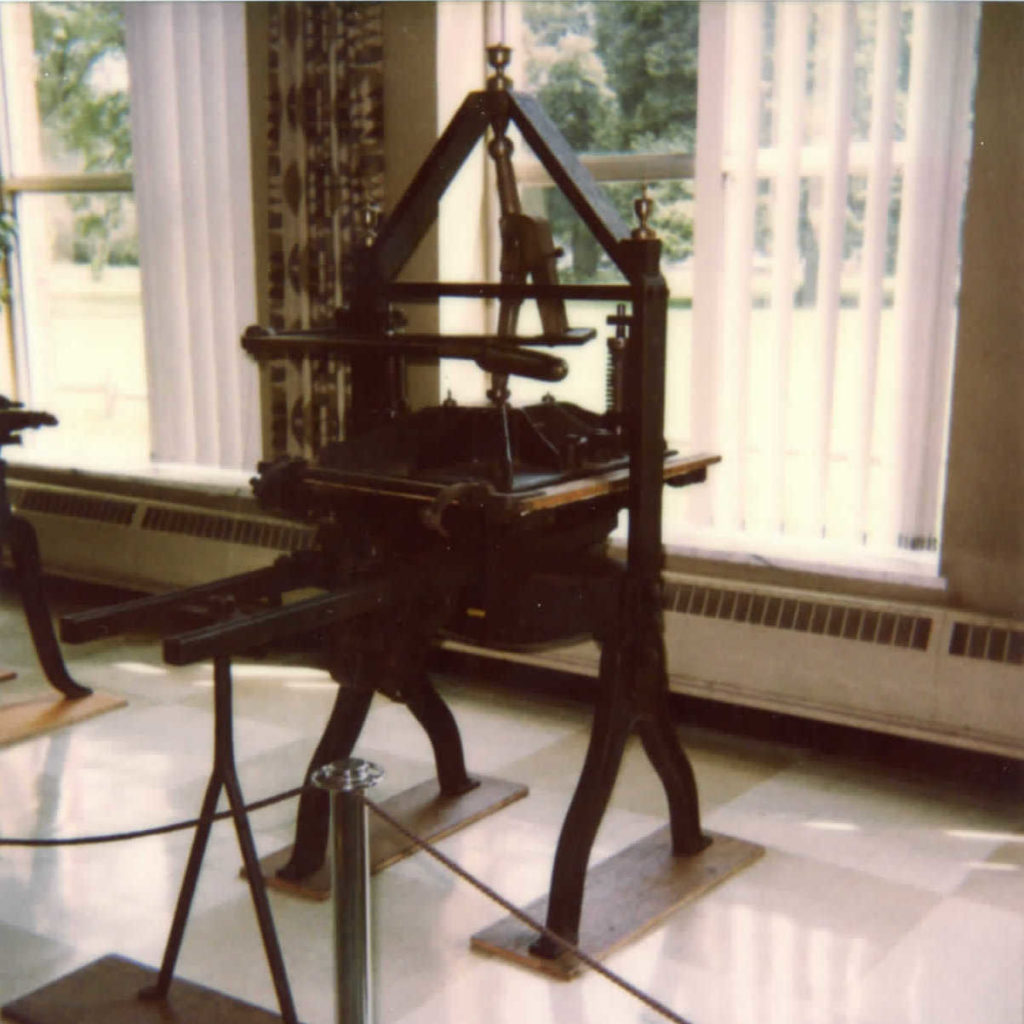

Left: Bronstrup Press at Fairleigh-Dickinson University, 1982.

Right: Bronstrup Press at the Gomez Mill House, 2018.

In the past, one of the key ways that the Seaport Museum allowed the public to access the collection around the United States, and particularly the East Coast, was through long-term loans. However, in recent years, long-term loans have been paused for a variety of reasons including but not limited to the fact that a number of states have passed old loan legislation in reaction to problems that arise where loans are left in museums for indefinite or long periods of time. Such problems include the amount of administrative work needed to properly manage the relationship and the required paperwork, the increasing opportunity of being “lost in translation” between staffing changes and the lender’s personal situation, and the confusion and misunderstanding that such objects could create if stored with collections items belonging to the borrowing institution.

Since limiting the duration of the loan to a shorter term helps avoid problems that arise when lenders lose contact or relocate, we improved our long-term loans with the Gomez Mill House by specifying an annual renewal expiration date within the loan agreement. This way both parties are required to touch base on a yearly basis, check-in on condition, insurance, and willingness to continue the loan, etc.[1]As of May 2019, when our governing Collection Management Policy has been updated, the South Street Seaport Museum makes loans of objects from its collections to qualified borrowers and may request … Continue reading

Gomez Mill House

The Gomez Mill House in Marlboro, New York, in the central Hudson Valley, has a fascinating history, and it is thought to be the oldest Jewish residence still standing in the United States. Luis Moses (or Moises) Gomez bought the land that surrounded the house in 1714, but it’s unlikely that Mr. Gomez lived there, although it is likely that at least some of his four sons did, at least sporadically. He was the son of an influential Spaniard, Isaac Gomez, a wealthy man so well-positioned that he advised the King of Spain. He was educated in London, and then the family moved to the Caribbean—there is firm evidence of Gomezes in Jamaica—and he might have lived on other islands as well. Jamaica flourished as a commercial center until 1692, when a tremendous earthquake demolished its main city, Port Royal. So in 1700, Luis Moses Gomez and his wife, Esther, moved to the fast-growing financial center of New York, Lower Manhattan, and to be precise, Maiden Lane, just south of the seaport.

Gomez was a trader and an entrepreneur. He built the Mill House as an outpost, a place to stay as he and his sons oversaw the trade in timber and limestone, commodities available in profusion upstate. When the Gomez family began doing business in the central Hudson Valley, there was no Jewish community there, and wouldn’t be until more than a century later. After Gomez, the house had many owners, some of them notable.

From 1772 to 1799, the house was owned by Wolfert Ecker (1730-1799), descended from a prominent Dutch family that arrived in New Netherlands in 1655. Ecker was a Revolution-era patriot, and he set up a local committee for safety and inspection that, according to Gomez Mill’s director, Richie Rosencrans, was one of the tools that local leaders established—a form of ad-hoc government to keep society’s basic rules in place once the British began to lose power but before formal local, state, or federal government agencies could take over.

Next—after some gaps—came the artistic and civic-minded Armstrong family, landed gentry who lived in the Gomez Mill House from 1835 to 1904. Among the various generations of the family, David Maitland Armstrong (1836-1918) was particularly interesting. He was a diplomat, a painter, and a renowned stained glass artist, whose works are still visible in the house. Maitland was largely responsible for creating the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which opened on February 20, 1872. In his obituary, the New-York Tribune stated: “Not only did he, in company with Robert Gordon and Dr. Nevin, first start the agitation for a representative museum in this city, but he also drafted suggestions for the carrying out of the project, with the result that the Metropolitan Museum as it exists to-day is largely organized on the lines he laid out.”

Another gap, and then there was William Joseph “Dard” Hunter (1883-1966), whose tenure was short, from 1912 to 1918, but had many intriguing connections with our Museum’s mission and collection. Dard was a printer, bookbinder, and a paper craftsman. In 1913, he built a paper mill adjacent to the pond and dam across the road from the main house, fashioned after 17th-century Devonshire cottages. Until then all the world’s handmade books were made by different masters in sequence—papermakers, typographers, printers—working separately with apprentices. Dard’s creations were the world’s first handmade books designed and constructed by one person, and his success inspired other Americans to begin producing handmade paper again.

Lastly, from 1918 to 1925, the house was owned by Martha Gruening (1889-1937), an American journalist, lawyer, and Civil Rights activist. With her, there was a bit of full-circle completion to her residency; like the Gomezes, Ms. Gruening and her family were Jewish.

Deaccessioning

In 2019, as part of the refinement of our printing history collection, we took a hard look at our collection of working printing presses, and when in 2020 the Gomez Mill House decided to end the loan, we had to make some decisions.

Over the past year or two, the debates, discussions, symposiums, and news about deaccessioning in museums flourished, but many misunderstandings about deaccessioning and museum collections remain both within and beyond the United States.

Here at the Seaport Museum we have been doing our part. We studied and analyzed some of the original and essential purposes of the deaccessioning process in museums, as well as looked at the process by which it has become—in some cases—a suspect practice. Among the many resources, webinars, and conversations we investigated is the recently published book by California museum consultant Martin Gammon, Deaccessioning and Its Discontents, which provided us with some wonderful guidance. One of the main findings of the publication is that deaccessioning has been an essential part of museum practice since the dawn of the museum experiment in the 17th century, and as curators manage the accumulation of multiple private collections into a growing public collection, they often come to realize the need to deaccession in order to refine the collection over time to ensure it has ongoing coherence and is improving through the evolution of each institution.

Deaccessioning has gotten a bad reputation only in the last three decades of the 20th century because of the significant pressure on leading museums to deaccession works in order to simply stay solvent and afloat—these pressures including decreased government funding, a detrimental U.S. tax reform act, and a booming art market. This burden has resulted in a situation where museums are more financially pressured than ever to sell off works for the wrong reasons—even though both the American Alliance of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors say that selling off artworks is only acceptable when the proceeds are used toward new acquisitions, not operating expenses, salaries, or capital projects.

The Seaport Museum chooses to deaccession objects for a few reasons. An item might not fit our mission or collections plan. Items with unknown provenance or otherwise lacking in historical value or usefulness are also candidates for deaccession. Poor condition or duplication are other reasons.

Since 2015, when we were both hired, we have approached both acquisitions and accessioning, as well as disposal and deaccessioning, in practical terms. We both believe deaccessioning is a fundamental business practice necessary for the responsible preservation and health of our collections.

Assessing candidates for deaccession is a slow and deliberate process. We have set guidelines for careful selection, which involves gathering all the information known about the item and then making a recommendation. The information and recommendations are reviewed and approved by a Staff Collections Committee, then by the Museum’s Board of Trustees, and, overall, guided by state statute. Depending on the condition of the deaccessioned piece, it may be transferred to another educational institution, exchanged, destroyed, or sold at public auction. The proceeds are restricted and can only be used to obtain new collections items or for direct care of collections. Going through a deaccessioning process allows us to complete targeted research on the collection, often increasing our knowledge about the objects we hold.

The Bronstrup was the third similar type of press after the R. Hoe Washington Hand Press, on view and used for demonstrations at Bowne & Co. at 207-209 Water Street, and the Cincinnati Washington Hand Press that we were also considering deaccessioning for redundancy reasons. As part of the refinement of the Museum’s printing history collection, the Bronstrup was then deemed not to be essential to tell the history of Bowne & Co. and printing in New York, due to her manufacturer and limited history at the Museum. So, after having her deaccession approved by the Collection Committee, we started to look for a new home for it.

International Printing Museum

Much of this story was made possible by a visit to Bowne & Co. from Mark Barbour of the International Printing Museum in Carson, California. The letterpress community is mighty but small, and smaller yet is the printing museum community. In early April of 2021, Mark happened to be on a trip to New York to install a press for a film shoot. The South Street Seaport Museum and the International Printing Museum have had an open dialogue for many years, but being on opposite coasts, it’s a rare treat to be able to physically visit each other’s collections. Mark had not visited Bowne & Co. for at least a decade, and a lot had moved around the Museum in that time. It was a great opportunity to reorient both the collections and mission of the Seaport Museum with a similar institution.

Part of what came out of his visit was a deeper understanding of where the missions of both museums cross over, and where they differ. The South Street Seaport Museum’s mission is fundamentally rooted in telling the story of the rise of New York as a port city. Printing plays a huge role in that story, but its role is in the service that printing offices offered to the financial growth of the city, and the technology that supported that rapid growth. The mission of the Seaport Museum is not to encapsulate the minutiae of technological development amongst similar printing equipment.

The Bronstrup is much better suited in the collection of the International Printing Museum—a collection which covers the incremental advancements in printing technology made throughout history. Transferring the Bronstrup from the Gomez Mill House to the International Printing Museum both helped the Seaport Museum refine its collection to best express its mission and increased the breadth of the collection at the International Printing Museum. We are thrilled that this press found such a good home, and we look forward to working together in the future.

Conclusion

Inventorying, reexamining old loans, and refining the collection can be a long, but rewarding process. Not only do staff rediscover lost collection items, they can also uncover lost stories that help us better understand the people who’ve lived and worked in the port of New York over the centuries. Removing an item that no longer supports the Museum’s mission leaves more collection care resources, storage space, and conservation budget for those pieces that still have research and education potential. When a collections item can better tell its story at another institution, like the Bronstrup Philadelphia Hand Press with our friends at the International Printing Museum, deaccessioning is especially rewarding.

Additional readings and resources:

American Alliance of Museums Code of Ethics

“Typographia, 3rd Edition” by Thomas F. Adams, Philadelphia 1845, p.272.

“The Cultural Logic of the Late Capitalist Museum” by Rosalind Krauss, The MIT Press, October, Vol. 54 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 3-17.

“American Iron Handpresses” by Stephen O. Saxe, Oak Knoll Books, 1992.

“Printing on the Iron Handpress” by Richard-Gabriel Rummonds, Oak Knoll Press & The British Library, 1998.

“Things Great and Small: Collections Management Policies” by John E. Simmons, American Association of Museums, 2006.

“Managing Previously Unmanaged Collections: A Practical Guide for Museums” by Angela Kipp, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

“Collection Ranking: Making deaccessions work for you” by Caitlin Podas, posted on October 23, 2019 on American Alliance of Museum Blog.

Bowne & Co.

Bowne & Co. is New York’s oldest operating business under the same name. Using seven historic presses from the Museum’s working collection, our resident printers continue the age-old tradition of job (or small batch) printing, creating individual designs using custom plates or historic fonts.

Visit Our Online Shop

We’re excited to announce our new Bowne & Co. Online Shop with a special selection of core offerings from Bowne & Co.

References

| ↑1 | As of May 2019, when our governing Collection Management Policy has been updated, the South Street Seaport Museum makes loans of objects from its collections to qualified borrowers and may request loans from other organizations or individuals only for exhibition purposes. The Museum does not accept or initiate indefinite or permanent loans. |

|---|